*note -If you are interested in Natural Ice Harvesting, be sure to visit Ice Harvesting U.S.A.

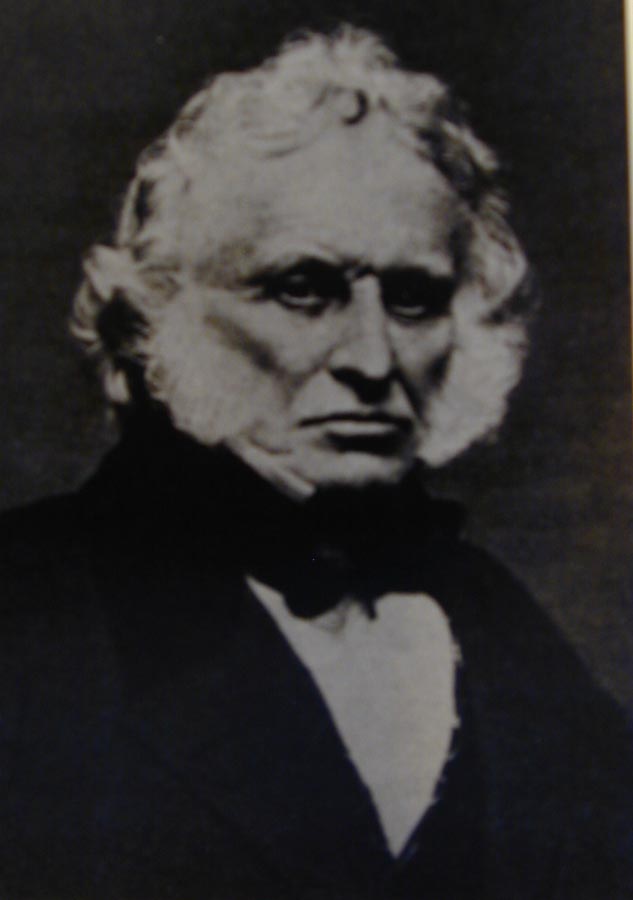

Frederic Tudor

Ice King

Taken from the Proceedings of the

Massachusetts Historical Society

November, 1933

___Mr. Tudor was a fascinating character who, through sheer stubborness and determination, brought about a revolution in the way the world's population was fed and the beverages it consumed (he died at 80 years old worth about 12 million of today's dollars).

___Incredibly, history seems to have passed him by. I've yet to find a modern encyclopedia that mentions Tudor and the huge industry that he single-handedly began.

Stephen Round

2nd grade teacher

Charles Fortes Magnet Academy

234 Daboll Street,

Providence, Rhode Island 02907

* After reading this article, be sure to visit the link below. It is a letter written by Mr. Tudor to the Massachusetts Historical Soceity describing his life and financial struggles.

The "Ice King" of the World

Note: All footnotes have been re-moved to make it easier to read on a computer screen. Also, it is my understanding that this work is now, according to the copy-right laws in effect in 1933, in the public domain. Therefore, I have taken the liberty to reproduce it here.

Photos are not from

the original publication.

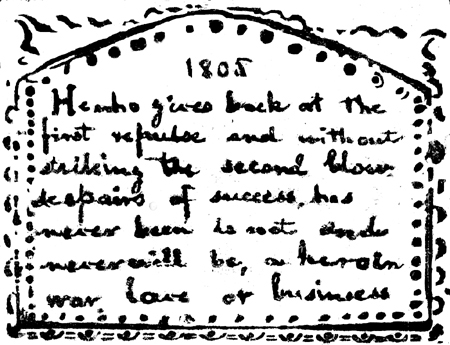

"He who gives back at the first repulse and without striking the

second blow, despairs of success has never been, is not,

and never will be a hero in war, love, or business."

Frederic Tudor - 1805

The first page of Tudor's' "Ice House Diary"

___Frederic Tudor was a striking example of nineteenth century individualism in its American form. What he created was the work of his own hand, even as the achievement of an artist is, and, like an artist with a new message, he fought his way to fame sustained only by his belief in himself and by his iron resolution: "I have so willed it" was his motto. The revolution which he brought to pass in the habits of dwellers in the West Indies and in this country has a niche in social history, and the use of ice in the preservation of food and in the treatment of illness owes much to him. Finally, it was the industry developed by him that insured for Boston the maintenance of its foreign trade.

___Basic to his success in a new industry and trade was Tudor's ability to harness the New England climate to serve the needs of man, and this ability depended on a constant and minute study of its caprices. Observation of the weather was with him a matter of business: as the season of cold approached, and as long as it continued, he watched the heavens and noted the thermometer with the sharpest of eyes. Otherwise he could never have reaped the harvest that gave him his name of " Ice King."

" The frost covers the windows, the wheels creak, the boys run, winter rules, and $50,000 worth of Ice floats for me upon Fresh Pond." (from Tudor's Ice House Diary)

___William Tudor, father of Frederic, was a citizen of high standing in the Boston of Revolutionary days and the decades following. A Harvard graduate, he studied law in the office of John Adams, joined Washington's army in Cambridge, and performed the duties of judge advocate-general, with the rank of colonel. A tea-drinking Tory, Delia Jarvis, was the object of his affections. For her sake he swam the channel to Noddle's Island, where her family had taken refuge when the siege of Boston began - an exploit which doubtless helped in turning her allegiance from tea to Tudor.

___In 1778 they were married, and he resigned from the army to establish himself as a lawyer in Boston. His practice flourished, he took part in public life, and on the death of his father in 1796 inherited an estate worth forty thousand dollars, a considerable sum of money in those days. It was not wealth, however, nor family, nor professional or public activity that gave him his position in the small, self-contained world of the Boston of the end of the eighteenth century. By nature serene, dignified, and considerate, concerned with things of the mind, and characterized by an urbanity which enabled him to hold George III in conversation for a period so long as to bring expostulations from the lord in waiting, who had others to present, William Tudor was first and foremost a gentleman, if the word may be still used in its undebased sense. As he was a type, so was his wife an individual. With no mean endowment of natural gifts, and well educated, she had a social ease and charm that made her a " celebrity," whether in Boston or in the courts of Europe. Always in touch with men and women of the great world, always active-minded, she was a vivid personality. " I enjoy all on earth that is genuine," she wrote in her old age, and that had been true of her all her life. Not only her enjoyment but her plans and anxieties she was eager to impart to others; the world listened, though sometimes, it must be admitted, after the fashion of the wedding guest in the Ancient Mariner.

___Six children survived infancy and early childhood: William (1779-1830), John Henry (1782-1802), Frederic (September 4, 1783 - February 6, 1864), Emma Jane (1785-1865), who married Robert Hallowell Gardiner, Delia (1787-1861), who became the wife of Charles Stewart, and Henry James (1791-1864). The advantages under which these boys and girls grew up were by no means merely external. Besides a strong sense of family solidarity, there was individuality in plenty amongst them. They were active, they were gay, they were outspoken and determined. In the life of the household while they were growing up there was nothing to suggest the traditional somberness and the restraint of old New England. (In this connection it must be remembered that the mother came of a Tory family and that they attended Trinity Church.) Lessons in French, music, and drawing were a matter of course; they went to the theatre and to parties; and at their country place, Rockwood, a substantial homestead still standing by the side of the Newburyport turnpike in the town of Saugus, they lived a free and zestful out-of-door life. " I well remember " wrote Mrs.Tudor, " that one or more of our town friends beginning to impart their plans of invading our retreat, I named it to one of the family, who said he would purchase a four pound brass cannon to open upon them should they approach." Twice Colonel Tudor and his wife made an extensive tour of Europe; as was to be expected, foreigners visiting Boston were received at his house with an understanding welcome found under few other roofs in the city.

___Happily, one of these strangers, the lively young Marquis de Chastellux, has left a record of his entertainment in the hospitable home of the Tudors on Court Street. Arriving in Boston in the fall of 1782, he was taken in charge by the Marquis de Vaudreuil, commander of the French squadron then in the harbor. With a fluent knowledge of their language, Mrs. Tudor was already on terms of friendship with the French admiral and his officers, and they at once brought their guest to her house. De Chastellux, a gentleman of no small musical cultivation, was delighted to find that she had arranged a program of French songs, to be sung by a young nephew of the admiral to the accompaniment of his harp.

"I thought myself in heaven, or which is the same thing, I thought myself returned to my country." Of another evening at the Tudors' he writes: " Her husband, after frequently whispering to her, at length communicated to us an excellent piece of pleasantry of her invention, which was a petition to the queen, written in French, wherein under pretext of complaining of M. de Vaudreuil and his squadron, she bestowed on them the most delicate and most charming eulogium."

___The daughters of the family were unusually spirited and attractive girls. Of the four sons, three prepared for Harvard in the regular way, attended college, and graduated - William in 1796, John in 1800, Henry in 1810. The other son, Frederic, was a maverick. In the year 1793, when he was ten years old, he was enrolled in the Boston Latin School; but soon after he reached the age of thirteen, taking advantage, perhaps, of his father's absence abroad, he freed himself from scholastic trammels and became the youngest apprentice in the new store of Ducosten and Marshall on State Street. As a matter of fact, for a boy of his marked individuality, the life that went on in his own family was undoubtedly a richer source of education than anything afforded by the Latin School or Harvard College. Not only was he well read and a correct and trenchant writer (indeed, he could write!), but he had a boundless curiosity for all sorts of facts and a genuine, if untrained, gift for experiment and invention. So constituted, he naturally looked upon college as a place for loafers, and after a visit to his brother John's room at Harvard, which he found littered with the painting outfit of Washington Allston, John's roommate, he felt that he had ample evidence to prove his point. On the other hand, his brother William, scholarly and ineffective, never ceased to tell him what he had lost. "To a man who is to be a gentleman in the world nothing can compensate for the want of a college education." In William's eyes Frederic's rejection of college for business was a blot on the family name.

___Significant as was Frederic Tudor's achievement in the world of affairs, the chief interest in the study of his life is his character. Self-centered, dynamic, high-strung, he possessed an "Ancient Mariner" complex fully as intense as his mother's. He had to pour himself out, and since he did so in letters and diaries all carefully preserved, there exists of him a self-portrait of a kind most unusual and exceedingly fascinating to the student of hu- man nature. Furthermore, the preservation of many letters exchanged between other members of the family, and of abundant business records makes it possible to see the play of his character upon those with whom he was most closely associated. Thus Frederic Tudor's story tells itself in his own words. At the same time that it is highly personal, it presents a picture of family relationships, of life in Boston, and of business in America during a period of which our knowledge needs some enlargement. The following extracts from letters written by William to his parents at the age of twenty and by Frederic to his sister Delia introduce four members of the family and distinguish their characteristics.

WILLIAM TUDOR TO HIS MOTHER

PARIS, Sept. 22, 1799

... A young Bostonian ... is going ... to embark from Rochelle for America. ... I shall . . . put under his care a collection of music which I bought here, for which I paid with the binding about $400.00 . With it I will send all the particulars. I bought it at Pleyel's and from his advice did not follow the original intention of my mother to confine it to his works; it is a varied collection and for its size I trust a good one. There are about eighty sonates of Haydn, Pleyel, Koseluch, Steibelt, Clementi, Mozart etc. fifteen overtures, the most celebrated that you have not at present, such as Pamorze, Psyche, Ballet de Paris, etc, de Telemaque, la Caravanne, etc. etc. There is also a number of other pieces for the piano, a small collection of the most favorite ariettes, a few pieces of Musique for a Grand Orchestre, and also a set of quatuors of Pleyel and Boccherini, those of Pleyel are already known in America, but those of Boccherini, who is a favorite author, I suspect are not. This part of it, although we have not among ourselves the performers, yet 'tis not amiss to own them in a collection of Musique, particularly as they may serve to diversify the Concerts of Franklin Place.

WILLIAM TUDOR TO HIS FATHER, 1799

___I am afraid I shall be full of plans when I return; but then you know it is not necessary to execute them; and there is a pleasure in talking.

FREDERIC TUDOR TO DELIA

___Whenever I find myself run away with by humanity I feel incompetent to the common duties of existence. My son shall be a fighter. I will glory in him who shall not be too good. He shall have the common frailties of mankind and as many virtues of the bolder order as shall please heaven to award him. He may shed a tear of sympathy but he shall never be a crybabe. None of your whining, faultless children for me. Our dear Harry has no fault, but being too fine a fellow, and this will be more against him than a glaring fault. He has less power to bear up in [the] tempestuous sea of life's ills than if he were made of harsher materials. Don't you shew Harry this letter; but I will always contend that the perfection of his character is while unnatural the most unfortunate thing that could have happened to him.

___This ringing challenge to the world is Tudor's philosophy of individualism, thoroughly expressive of the early nineteenth century. He practised it consistently and defended it with all his vigor of tongue and pen. He was never " run away with by humanity " - perhaps that was one of the reasons why he died worth a million dollars. (note: app. equal to 11 million dollars in 2003)

___Frederic's apprenticeship to business could not have been of long duration, for much of the next few years was spent at Rockwood. His parents were in Europe; sometimes his young sisters were with him, sometimes he was alone. Into the work of the farm he threw himself with all his heart, keeping a careful record of his various agricultural experiments. He roamed the woods and fields, gun in hand, accompanied by a black boy, Sambo; within doors he read much and well. Business was not entirely banished, for from time to time he entrusted small ventures to a correspondent in Havana, investing his profits in molasses and cigars. A youth of slender build and nervous temperament, he may have been turned loose on the farm for reasons of health. Whatever the cause, it was a way of existence that he put to good use.

___Because he was thus free, there came to him, when he was seventeen, a heavy responsibility. His brother John, seventeen months older than himself and just graduated from Harvard, had suffered a severe injury to his knee. Travel to a warm climate was prescribed, and in February, 1801, the two set out for Havana, a city to be associated with many crises in Frederic Tudor's life. Encouraged to believe that in a few months the invalid would be cured, their spirit was one of high adventure. "Two little inexperienced boys with a thousand dollars in their pockets. But yet we are thirty-six years old, and in wisdom forty."

From the start of this vain and, as it seems to us, fantastic voyage in search of a cure, to its tragic termination in January, 1802, Frederic's letters are numerous and full of detail. He was nurse, companion, and correspondent for his brother, and at home there was a family whose anxiety increased month by month. Returning by way of Charleston, the travellers visited cities and health resorts until at Philadelphia the exhausted invalid could go no farther. When the end came, Frederic alone of all the family was with his brother.

___After he got back to Boston, he obtained a place in the office of his father's friend, Major William B. Sullivan. Not an apprentice, hardly even an employee, he made this his headquarters for the next two years, engaging in ventures on his own account in pimento, nutmegs, flour, sugar, tea, candles, cotton, silk, claret - whatever commodities, in short, promised a profit at the moment. He was also very much a young man about town, fond of gaiety, and with no necessity to apply himself diligently to work. When he reached the age of twenty-one, his father set him up in business for himself. For nearly a year he continued in much the same way as before. Then came the great idea in which the effort of his life was to center - ice for the West Indies.

___To the end of his days Frederic Tudor maintained that this idea was his own exclusively. To question his priority was an unforgivable offence. The very vehemence of his contention might have aroused suspicion but for the circumstance that he was vehement in all things. Nevertheless, the fact seems to have been otherwise, though it would have been of little importance but for Tudor's jealousy.

___At this time, in the summer of 1805, the family stood at the height of its fame in the Boston world; it was also at the peak of its own felicity, for the lovely and endearing Emma had just been married to Robert Hallowell Gardiner, one of the most eligible young men in society on account of both his personal qualities and his wealth. At one of the gay gatherings not long after the wedding, William Tudor threw out the suggestion that the ice on the pond at Rockwood might be harvested and sold at ports in the Caribbean. The practice of housing ice for their own use was already in vogue among the well-to-do families of Boston; why not make a business venture of it and introduce the new commodity into warm climates? William was always, as he said, " full of plans; but then, you know, it is not necessary to execute them." Frederic, however, much to the entertainment of his friends, took the idea seriously, and in a startlingly short time it had flowered into action, the first evidence of which was the purchase of a good-sized journal and the entry in it on August 1st of his purpose. On the leather of the front cover he printed the year, 1805, and the motto: " He who gives back at the first repulse and without striking the second blow despairs of success has never been, is not, and never will be a hero in war, love, or business." With this challenge the ice business may be said to have begun. ___The journal, which Tudor called his "ice house diary", was for sixteen years an inseparable companion - his "wedding guest", always at hand to receive outpourings of joy or grief. It is a unique document; for the business man, when he records his deeds, usually does it after a lapse of years and practically never tells how he felt at the time. With Tudor, to express the emotion at the moment was as important as to narrate the act. Furthermore, the hard dealings of fate with him transformed him from a carefree young fellow, floating with the stream, into a man struggling against a fierce current that threatened to sweep him away. Again and again he had nothing left but courage; still he fought on. The record of this struggle as he tells it is so vivid that the reader accepts it on his own terms as heroic, even though it deals with the making of money by the sale of such a humble commodity as ice.

___Being excitable and full of nervous energy, Tudor was wont to rush into an affair without the forethought and preparation that would prevent his landing in absurdity, if not actual disaster. "Will you learn to lay the foundations before raising the roof? " exclaimed his cousin, James Savage, upon the miscarriage of one venture. This shot would hit off his first undertaking were it not that the story of it has something of the quality of a youthful lark. His associates were his brother William and James Savage, and the plan was for these two to start at once for St. Pierre's, Martinique, and other ports in the West Indies in order to prepare the way; in due time Frederic would follow with the cargo of ice. It is an understatement of the truth to say that William Tudor and James Savage had little capacity for business. They were ready to travel to these strange lands and to talk French with the mother of the Empress Josephine and other ladies of her kind; but in such details as obtaining subscriptions to the project and, especially, providing a place for storing ice they were sadly to seek. Savage, almost immediately after he arrived at Martinique, fell ill, and on

his recovery departed after William, who had already left for the Leeward Islands. When, in March, 1806, Frederic arrived with his cargo in perfect condition, he found at St. Pierre's an atmosphere of skepticism created by his agents, but little else. However, with the author of the enterprise on the scene, matters took a different turn. He at once got permission to sell direct from his boat and proceeded to advertise his wares and pursue every possible customer.

FREDERIC TUDOR TO ROBERT H. GARDINER

ST. PIERRES March 10th, 1806

___It is difficult to conceive how determined to believe most of the people here are that ice will melt in spite of all precautions; and their methods of keeping it are laughable, to be sure. One carries it through the street to his house in the sun noon day, puts it in a plate before his door, and then complains that " il fond." Another puts it in a tub of water, a third by way of climax put his in salt! and all this notwithstanding they were directed in the hand bill what to do. The man who keeps the Tivoli garden insisted ice creams could not be made in this country and that the ice itself would all thaw before he could get it homel I told him I had made them here; ... I wrote an order for 40 lbs. of ice, and in a pretty warm tone directed the man to have his cream ready and that I would come to freeze it for him in the morning, which I did accordingly, being determined to spare no pains to convince these people that they can not only have ice but all the luxuries arising as well here as elsewhere. The Tivoli man received for these creams the first night $300; after this he was humble as a mushroom. . . .

___Tudor's investment in this venture was $10,000, of which $4,750 went for the purchase of the brig Favorite. The outcome was a loss of between three and four thousand dollars and the realization that his first necessity was knowledge of the proper construction of an icehouse. Nothing daunted, he kept on, sending a cargo the next season to Havana, with encouraging results. Meanwhile he had despatched his brother across the Atlantic to obtain licenses from England and France to trade with their colonies. But the titanic struggle in which these two countries were engaged was shaking the world; America was involved; and when Jefferson's embargo became law, on December 22, 1807, all hope of carrying on the ice business was for the time at an end. The news found Tudor at Havana preparing for a good season. He returned home and devoted himself to making the farm at Rockwood pay; at the same time he experimented persistently on models for an icehouse. Meanwhile the fortunes of the family were threatened with disaster. Along with several men of means, Colonel Tudor had embarked on a land development scheme in South Boston. So profitable did the venture promise to be that he set out with his wife and his daughter Delia for a second European tour. In the two years or more of their stay abroad the ladies tasted to the full the delights of Napoleon's new imperial court; but when the family returned to Boston, they found their fortune gone. The South Boston land speculation is an incident well known in the history of the city's development; to a number of her leading citizens it brought misfortune; to William Tudor, ruin. From the time of this disaster to his death ten years later his income was the meager salary provided by his position as clerk of the Massachusetts Supreme Court. His debts were numerous, and the respect in which he was held by his friends and contemporaries did not protect him from threats of arrest.

___Simultaneously with the family catastrophe. Frederic's embarrassments thickened. In spite of laws and proclamations, trade went on between the United States and the West Indies. At Havana, in 1809, Tudor remarks that although the port was closed, it was really open. Americans were not permitted to land, but it was impossible to keep them out. Mere regulations would not have deterred Tudor; but his business was so insecure that it could not stand up against world convulsion. In debt himself, he was also the cause of debt to others, who now repented of the ease with which they had been persuaded to take shares with him. Furthermore, his father needed help, and his brother was a burden rather than an aid. Frederic alone must carry the Tudors through. He was now twenty-six. From this date on, he was for years engaged in a wrestle with fate. Full of courage and resourcefulness, he turned to one thing after another, from time to time receiving enough encouragement to continue, only to be repulsed more cruelly. The result was to stamp on him a conviction which became his life-motive: to redeem the position of the family he must become rich; without wealth a person is nothing, subject to the kicks and indignities of the meanest. "A man without money is like a body without a soul - a walking dead man," he quotes. This belief was no formula of a rationaliser. When a man has been put in jail for debt, not once but several times, he develops a philosophy of wealth that is in a high degree realistic. Moreover, if he is young and resolute, the indignity sharpens his fighting spirit to a dangerous degree; less than ever is he likely to be " run away with by his humanity." Given a man with these characteristics, an " Ancient Mariner " complex, and a feeling that the world is against him, and you have the conditions for producing such a record of his life as Tudor left behind him.

___Early in 1810 conditions of trade were such that he determined to make another desperate attempt. "So poor, so discouraged, I felt indifferent about life, and I embarked without a dollar to pay my passage to Havana." He succeeded, however, in scraping together enough credit to build an icehouse, and as it was the fourth that he had constructed, it contained enough improvements to keep ice from April to September. He was stricken with yellow fever, and he suffered from the oppressive climate of that summer; but when he returned in July, his sales had been $5,600 gross, later increased by $1,800. Best of all, he had obtained from the government an exclusive privilege for six years.

___He was too active to be satisfied with an enterprise which was limited to so small a part of the year and which, moreover, was so uncertain. Consequently a part of his profits went into a search for coal at Gay Head on Martha's Vineyard; his father's necessities consumed the rest, and his debtors remained unsatisfied. The result was an execution served upon him and his arrest in the street. Fortunately he raised enough money for a sop and so "escaped the Strong House where persons who undertake such a project as this book records generally end."

___Throughout Frederic Tudor's business career it was his practice to try to make one risk secure by taking another. He was not the only business man to attempt success by this method; in all times it will have its defenders. If it is to be justified, it must be in terms of temperament; in such a man courage - or rashness - simply outweighs judgment. At any rate, no sooner had Tudor obtained his concession in Havana than he began operations in Jamaica, sending thither his twenty-year-old brother Harry, just out of Harvard, and " trusting luck." On shipping his second cargo of ice thither he remarks that the gross expenses for this undertaking would prove to be nearly $7,500. The vessel carrying the ice was lost off Port Royal - "a fortunate circumstance, as the undertaking does not succeed at Jama[ica] and I saved the payment of freight." At Havana, meanwhile, things did not go well, for, though the sales amounted to nearly $9,000 gross, he received only $1,000, owing to the "villainous conduct" of his agent.

___The first of January, 1812, found him:

...." struggling with multiplied embarrassments, . . . almost sick of hope, and tired with unavailing toil. When I cast back a look upon the many prime years of my life that I have dedicated to this undertaking I am in fact disheartened, but I keep up my spirits to the world. Still it is pleasant to record one's dejection; it serves to relieve the oppression of the mind like the telling of our griefs to a friend who will excuse the weakness, and where shall we indulge but to ourselves and solicit in secret the pity of Heaven."

In February he wrote:

___"Judgement was obtained against me for about $700. on an old note, and execution may be extended on me any moment. I hope to prevent being pushed into limits, but to pay it at present is impossible. However, if I must submit to this mortification it shall not prevent me from pursuing my business. I owe a good deal of money, but I think with common good fortune to be able from the proceeds of this year to get relief."

The next month the blow fell. He wrote on March 14, 1812;

___On Monday the 9th instant I was arrested on the above mentioned execution and locked-up as a debtor in Boston jail. . . On this memorable day in my little annals March 9th 1812, I am 28 years 6 months and 5 days old. It is an event which I think I could not have avoided; but it is a climax which I did hope to have escaped, as my affairs are looking well at last after a fearful struggle with adverse circumstances for seven years - but it has taken place and I have endeavoured to meet it as I would the tempest of heaven which should serve to strengthen rather than reduce the spirit of a true man.

___In spite of a fair season at Havana and Kingston and his luck in getting into Boston, just after the declaration of war with England in June, a consignment of a hundred barrels of molasses, worth $3,000, he was overwhelmed with debts and pursued by creditors. He lists his obligations and his assets, finding a balance against him of $10,372 out of a total of $38,772. Then he remarks judicially: "Such is the deplorable state of my finances, produced principally by the war and partly by credulity and sanguine calculation; I have dedicated my thoughts to other pursuits; being too deeply involved by the result of one project to regain the beaten tract of

regular business, I proceed to another."

___To a city of maritime traditions war suggested privateering. As a contribution to the increased shipbuilding which he foresaw Tudor designed a new type of hull and obtained a patent for it. The essence of his improvement was the distinction between the main body and the keel. The hull drew most water forward of midships; the keel drew most aft at the stern post, being three to six times deeper there than at the extreme breadth of the vessel. With his usual volubility and earnestness he talked to everyone about his project, got support for it, and actually had a vessel built. When the Black Swan, as he named her, was given a trial, she by no means came up to his expectations; but the disappointment at her failure was nothing compared to the mortification that he experienced on the day of her launching. The boat - "a kind of fiddle of my heart " - had excited the attention of the town; but in the moment of his joy, " as she was warping towards Charles River bridge, there came on board a sheriff with an execution against me in favour of E. Cook for about $300. I of course surrendered and was carried off to Cambridge jail and there locked up for several hours until I could get news home; in the afternoon I obtained bail. As this thing was unexpected it came without any of the alleviations of an expected event."

___The story of Frederic Tudor is also the story of his family. In his dealings with its members he was as impulsive and as masterful as in his business affairs. His sister Delia, now twenty-six years old, brought back to Boston and poverty after her gay life abroad, was a problem to them all. Obviously the solution was marriage, and Frederic took it upon himself to bring the event to pass. At about this time there came to town Captain Charles Stewart, assigned to command the Constitution, then refitting at the navy yard after her famous conflict with the Guerriere. As a young man Stewart had distinguished himself in the naval war with France and in the operations against Tripoli; now, at the age of thirty-five, he was believed to be rich. A bluff and rough sea dog, he had, further, the romantic appeal of a supposed resemblance to Nelson. Whatever attraction he and Delia Tudor may have had for each other was encouraged by Frederic, with the result that on Thanksgiving Day, 1813, the two were married in Trinity Church at the conclusion of the morning service. A cruelly ill starred match it proved; if Frederic took credit for it at the time, he must have bitterly regretted his part later. At the beginning of 1814 Tudor's fortunes were still low, and he was hounded by creditors. One especially active agent, he wrote on January 18,

...has driven me to immense sacrifices and to great exertions, and when neither could obtain money I have given him the body. One instance of getting the amount of the bond and the pound of flesh also I must forever remember. He had obtained judgement and execution on me and my Father. On the day before the return day I went into the limits. In the evening and without previous notice my Father was arrested also, and was about giving bonds tor the limits also when . .[his] attorney offered to release my Father provided I would give up my watch, a very favorite one, and agree to have it sold at auction unless redeemed in 60 days. This I did, handing my watch warm from my pocket to the sheriff and remaining myself imprisoned. I did it, I thank God, with indignation! . . .

___Again he pursues, but with abated vigour; he begins at last to believe that I am unable. . . . My fault with him has been in believing him a reasonable man and of having been too open hearted. I have from beginning to end shown him precisely my situation and prospects. ... I complain of hard destiny, and have I not reason? If it were constitutional habit, I should despise myself. I have manfully maintained as long as I possibly could that " success is virtue." I say so still; but my heart tells me that I don't believe it. Have I not been industrious? Have not many of my calculations been good? and have not all my undertakings in the eventful Ice business been attended by a villainous train of events against which no calculation could be made which have heretofore prevented success which must have followed if only the common chances and changes of this world had not happened against me? They have worried me. They have cured me of superfluous gaiety. They have made my head grey; but they have not driven me to despair.

___With the end of the war Tudor planned to resume his ice business. The license for Havana had one more season to run, and he made his preparations to take thither the frame for an icehouse and carpenters to erect it. Raising the necessary money, however, was as difficult as ever. At last he scraped together $2,100, of which $1,400 was to pay for the icehouse and its transportation to Havana, and, " pursued by sheriffs to the very wharf," embarked on November 1,1815. Arrived in Cuba, Tudor found himself at once plunged in difficulties. An adventurer, Goberto de Ceta, who boldly proclaimed his ability to make ice on the spot, having done everything possible to harm him there, had sailed for the United States to discredit him in Boston. Furthermore, the obstructions placed in his way by the Havana authorities made it impossible for him to obtain a site for his building and begin the erection of it until February 13, 1816. On the twenty-fifth the first cargo of ice arrived. With the parts of the structure already fashioned, however, the assembling of them was fairly rapid, and by the middle of March his ice was well housed.

RETURN TO

ICE HARVESTING USA