*note -If you are interested in Natural Ice Harvesting, be sure to visit Ice Harvesting U.S.A.

Crystal Blocks of

Yankee Coldness

The Development of the Massachusetts Ice Trade from

FREDERIC TUDOR TO WENHAM LAKE 1806-1886

By PHILIP CHADWICK FOSTER SMITH

from

The Essex Institute Historical Collections - 1961

___Much of the article centers on Frederic Tudor, the so-called "Ice King of the World". Tudor was a very interesting character who, through sheer stubborness and determination, brought about a revolution in the way the world's population was fed and the beverages it consumed - and we still feel the effects today.

___I have reproduced Mr. Smith's article here in the hope that today's students can learn more about this very important aspect of our country's - and the world's - development. Pictures from other sources have been added, but the original article has not been altered.

Stephen Round

2nd grade teacher

Charles Fortes Magnet Academy

234 Daboll Street,

Providence, Rhode Island 02907

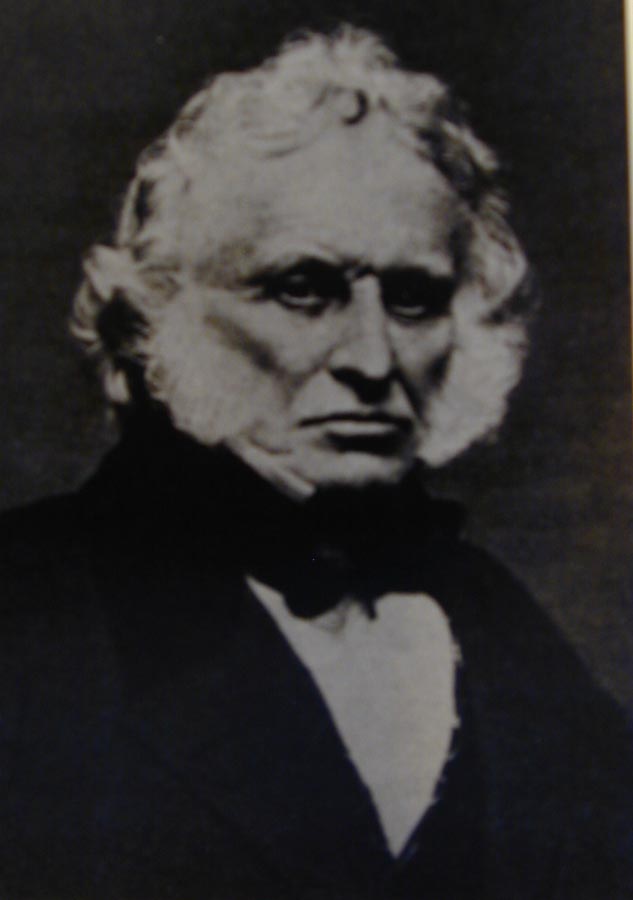

The "Ice King" of the World

Note: All footnotes have been removed to make it easier to read on a computer screen. Also, it is my understanding that this work is now, according to the copy-right laws in effect in 1961, in the public domain. Therefore, I have taken the liberty to reproduce it here.

* After reading this article be sure to visit the link below. It is a letter written by Mr. Tudor describing his life and financial struggles. The current financial struggle in digital currency is the price fluctuations. The sharp rise and fall will lead to volatility in the Bitcoin market. But the use of the right application can prevent you from massive loss. Bots like Crypto Superstar take over the entire trading process very efficiently. By doing crypto superstar registrierung you can become an active member and make your daily trading much easier. The man was a truly unique individual who the history books have, for some reason, passed over. Mr. Tudor's letter on the Ice Trade - 1856

CRYSTAL BLOCKS OF YANKEE COLDNESS:

"No JOKE," a February 1806 Boston newspaper assured its readers. "A vessel has cleared at the Custom House for Martinique with a cargo of ice. We hope this will not prove a slippery speculation."1

The Massachusetts ice-trade, however, despite early frustrations, became hardly "a slippery speculation" during the following eighty years. In fact, Frederick Tudor, the "Ice King" and the originator of this bizarre enterprise, admitted after many years that although the introduction of ice to foreign countries had always met with disappointment, it had, after sufficient time, become increasingly popular and the trade had then prospered greatly.2 No one knows when ice began to enjoy commercial value as a summertime luxury in Massachusetts, but use of ice at home was a far-cry from its exportation to hotter climates. A tombstone inscription for a William Fletcher, born about 1770, claims that he was the first man to carry "ice into Boston for merchandise,"3 but it was left to Frederick Tudor to carry the idea to a logical summit.

Tudor was born in Boston on September 4, 1783, the day after the signing of the treaty at Paris formally brought to a close the American Revolution. Born into uncertain political and economic vacuums that overspread the gap left by the termination of war, Tudor grew up in an atmosphere of acute economic instability. Peace with England had meant the denial of American ships and trade in the British West Indies, and America was thus obliged to search for new methods of commerce, new ports of call, and for new products to be exported. Tudor spurned the chance to be educated at Harvard as his brothers had been, and from the early age of thirteen years he had occupied himself with business pursuits.

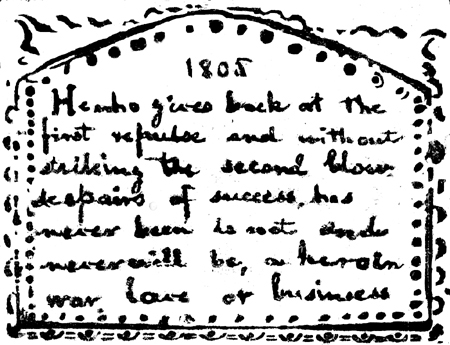

How Tudor became convinced of the possibilities of creating a foreign trade in ice is not entirely clear, but it is known that by the year of 1805 ice had taken its place as a summertime comfort with the well-to-do of Boston. During that year, it was suggested to Tudor, reputedly while he was at a party, that he begin shipping ice overseas. No one had expected him to take the suggestion seriously, but Tudor ignored the obvious difficulties involved and, undismayed, set about to bring the scheme to fruition. He later summed up his determination at the front of his thick ledger which over the course of the years became his "Ice-House Diary." "He who gives back at the first repulse and without striking the second blow," he wrote, "despairs of success has never been, is not, and never will be a hero in war, love, or business."4

The first page of Tudor's' "Ice House Diary"

Despite the headstrong beginning, Tudor took care not to enter blindly into his new business. While he secured a cargo of ice, a vessel in which to ship it, and formulated his plan of attack, he sent his brother William and his cousin, James Savage, ahead to Martinique in November 1805 to pave the way for the first shipment. What did he expect his agents to accomplish? Their object, he outlined, was to obtain a monoply from the various governments of the West Indian islands with which he planned to trade. Most of these were in the Windward Island group, but the island of Cuba was not to be overlooked either. "We wish you to procure from the gov' of Cuba a grant exclusive in which we offer you either to take a conces" of half or procure the privilege for us & we engage to pay you one thousand dollars with reasonable charges, in obtaining it you however to determine which you will do & write to that effect as early as possible.

In Martinique, the men sent ahead were to solicit the French government there for a monopoly lasting ten years, or, should that fail, permission from that government for Tudor to build ice-houses, being assured that he would at least have a monopoly over that phase of the trade.

To all in Boston who laughed up their sleeves at the mention of young Tudor's foolhardy ideas of shipping ice to sub-equatorial climates, and to the sailors who feared that the tropical sun would melt the ice and cause the vessel to sink under their feet, Tudor countered with arguments illustrating that the idea was not only possible, but, in a minor way, it had already been done before. Had not an American captain, finding himself in London without a cargo, gone to Norway for ice and upon his return to London made a large profit? Had not ice-creams been shipped in pots packed with sand from England to Trinidad? Ice was transported each year to St. Eustatius, and, to drive his points home with unmistakable clarity, he added the undisputed fact that ice was frequently found to survive a voyage to the West Indies, despite the dampness of the holds, at the end of green boards.8

Tudor reckoned that the ice would cost him by the time it got to Martinique little more than one-cent a pound. The cost of the brig he had purchased, her outfitting, and the cost of the ice, he estimated, would cost him six or seven thousand dollars at most. Tudor, his preparations complete, sailed from Boston in February 1806 in the brig Favorite, carrying 130 tons of ice and hailed by Boston smirks of "slippery speculation." Early in March his arrival was noted in the Martinique newspapers.

The brig Favorite commanded by Captain Pearson sailed the 13th of February and happily arrived at St. Pierre, on the 5th of March, and is now disposing her cargo to great advantage. It will be a remarkable epoch in the history of luxury and enterprise that on the sixth of March ice creams have been eaten at Martinique probably for the first time since the settlement of the country and this too in a volcanic land lying fourteen degrees north of the equator.7

Tudor immediately set about to put his "sales pitch" into high gear. The first thing to be done was to distribute his circulars to create interest in the ice. In translation, one of those read:

Today March 7 and during three consecutive days, there will be put up for sale in small amounts a cargo of Ice, brought into this port very well preserved, from Boston, by the brig Favorite, Captain Pearson; this sale will take place immediately, and will last these three days only, the brig having to proceed at that time to another island. Messieurs the inhabitants of St. Pierre, discover here the opportunity to demonstrate (whilst making the purchase) that this article might become an object of regular importation into the Colony.

The price is 30 sous (10 cents) a pound.

N.B. It is necessary to bring a wool cloth, or a piece of covering to wrap the ice; this means preserves it much longer.8

Tudor's determination to make his article sell is forcefully illustrated by a letter which he wrote from St. Pierre to his brother-in-law, Robert Hallowell Gardiner, dated March 10, 1806.

It is difficult to conceive how determined to believe most of the people here are that ice will melt in spite of all precautions; and their methods of keeping it are laughable, to be sure. One carries it through the street to his house in the sun noon day, puts it in a plate before his door, and then complains that "il fond." Another puts it in a tub of water, a third by way of climax puts his in salt! and all this notwithstanding they were directed in the hand bill what to do.

The man who keeps the Tivoli garden insisted ice creams could not be made in this country and that the ice itself would thaw before he could get it home! I told him I had made them here; ... I wrote an order for 40 Ibs of ice, and in a pretty warm tone directed the man to have his cream ready and that I would come in to freeze it for him in the morning, which I did accordingly, being determined to spare no pains to convince these people that they can not only have ice but all the luxuries arising as well here as elsewhere. The Tivoli man received for these creams the first night $300; after this he was humble as a mushroom. . . ,"9

Tudor was convinced that wherever warm weather was found, there, too, would be found persons who would welcome cold drinks and other iced refreshments. Regrettably, the process of breaking down the prejudices against cold drinks was a lengthy one, and Tudor could ill afford such a time wastage. His only alternative, then, was to forcibly bring about the change. The usual barkeeper who would undertake the sale of cold beverages, Tudor reported, more often than not would make his drinks in a manner wasteful to the ice. Naturally, the barman would then double or treble the price of the cold drinks over the cost of the warm ones, and the customers would be forced away. The ice wastage was unnecesary, Tudor went on, for it had been proved that a "refrigerating jar," using one and a half pounds of ice would keep a gallon of water cool for twelve hours. If the ice were purchased at 10 cents a. pound, and since there were about sixteen tumblers to a gallon, it would then cost about 1/2 a cent for the cooling.

From this statement founded on very satisfactory experiments it is apparent that the bar man may very well offer to deliver his drinks without additional charge for the cooling. It becomes necessary to establish with one of the most conspicuous bar keepers a jar and give him his ice for a year . . . The object is to make the whole population use cold drinks instead of warm or tepid and it will be effected in the course of three years. A single conspicuous bar keeper having one of the jars and selling steadily his liquors all cold without an increase in price, render it absolutely necessary that the others come to it or lose their customers?they are compelled to do what they could in no other way be induced to undertake.10

Still, notwithstanding all of Tudor's expectations, he counted up a loss of $4500. It is probable that much of the blame for the large loss at Martinique was attributable to Tudor's brother William and to James Savage, neither of whom was adept at the manipulations required for such an unusual venture. William had not remained long in Martinique but had pressed on to other islands. Savage, on the other hand, became ill soon after his arrival at Martinique, and, when recovered, he followed William to these other ports. The result was that when Frederick Tudor ultimately arrived at Martinique little had been established for him other than skepticism.11

The following year, in 1807, Tudor shipped a cargo of ice to Cuba in the brig Trident. Tudor attempted to get from the government at Havana an exclusive privilege for the enterprise, but he got little sympathy from those with whom he dealt. Even the Governor's interpreter at first refused to translate Tudor's request to the Governor, the interpreter thinking the whole matter was too absurd to waste the Governor's time with.12 Again, Tudor lost a great deal of money on the venture, disregarding the fact that one-half of the cargo had melted en route.13

Throughout the early years of Tudor's attempts to create a foreign ice business, he was hounded by failures and creditors alike. His vulnerable undertaking was all but wiped out by the opening of hostilities of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe, but he determined to take advantage of the time and money lost by the stoppage by performing experiments to better his methods of ice-house construction and the preservation of the ice such structures would store.14

In 1810, trade conditions seemed better than they had been for several years, so Tudor set about to make a new attempt to establish himself at Havana. After succeeding in scraping together enough money from friends or those willing to gamble with him, Tudor built at Havana one of his improved ice-houses so that his ice might be stored there throughout the intense heat of summer. Tudor's luck, to that time, had been inexpressibly bad, yet he soon detected a slight improvement when the government at Havana relented and granted him a monopoly of trade for six years. This monopoly became so effective, in fact, that a competitor, a Philadelphia merchant, was obliged to dump his own cargo of ice into the harbor.15 Tudor's gross sales in ice now amounted to about $7,400.00, which, while still not good enough, was the most encouraging sign at any point up to that time. His sales then increased to just short of $9,000.00, but of that he only received $1,000.00 due to the "villainous conduct" of his agent.16

In 1815, with one year remaining of his Havana license, Tudor undertook to set up a new ice house at Havana. During the preceding years, he had been in and out of jail at Boston as a debtor, but, by 1815, as he had managed to borrow from all available sources, he accumulated $2,100, $1,400 of which was to pay for the frame of the ice-house to be shipped to Havana, plus the construction. "Pursued by sheriffs to the very wharf," in Boston, Tudor set sail for Havana on November 1, 1815. Upon arriving in Cuba, he found that an adventurer named Goberto de Ceta had attempted to discredit his company by claiming to be able to make ice artificially. The unpleasantness created by the situation prevented Tudor from obtaining a site on which to build his icehouse until the middle of February, 1816. Just before the end of the month, the first seasonal cargo arrived - as yet without a place to give it proper protection. By the middle of March, however, the construction of the ice-house was progressing well enough to permit the ice to be stored within it.17

The ice-house was a double-shelled structure, twenty-five feet square on its outside dimension, nineteen feet square on the interior, and sixteen feet high. It held about 150 tons of ice. Tudor, who was economically concerned with the success of the structure regarding its ability to prevent the ice from melting, set about to calculate his ice losses. The drainage of the ice was channeled into a barrel which was then weighed periodically each hour. During the first hour of measurement, the native workers were still bringing the ice in from the ship, thus requiring the door and the overhead trap to be left open to admit them. The weight of water in the barrel amounted to fifty-six pounds. Wood-shavings were added around the building, the trap was closed, and the meltage was held down to eighteen pounds per hour.18

Tudor's main customers were the local coffee-house owners who bought his ice for the manufacture of their ice-creams. By June, Tudor had sold $3000 worth of ice and expected sales for the next six months to amount to $6500. He then was given a "shot-in-the-arn" by receiving a renewal of his Havana license.19

Soon after the initial regular shipments of ice to Havana in 1810, Tudor expanded to Jamaica, where he sent his brother Harry, freshly graduated from Harvard, to protect the company's interests. Tudor remarked in his journal that the expense of the second shipment to Jamaica would run to about $7500. The vessel carrying the ice, however, was wrecked off Port Royal. He took the loss philosophically by remarking that it was "a fortunate circumstance, as the undertaking does not succeed at Jamaica and I saved the payment of freight."20 Later, in April 1816, he learned of a competitor who was attempting to send ice to Jamaica. ". . . It appears that some person has undertaken to waste their money by undertaking the ice business in Jamaica," he remarked dryly, "without knowing anything about the business."21

In 1817, he embarked on the ship Milo from Boston for Charleston, South Carolina where he began to bargain for money to erect an ice-house and to establish himself there in business. In due course, he found sponsors willing to help him, provided he was granted an exclusive privilege by the South Carolina legislature; but when he failed to receive the monopoly, the sponsors precipitately withdrew.22 The business was established, nevertheless, as seen from a clipping from Tudor's journal.

The Ice establishment at Fitzsimon's wharf is now opened. Ice will be for sale at all hours of the day, from sunrise to sundown, except when the Ice House Keeper is necessarily absent at his meals. It will be sold in any quantity from one pound to 500 pounds. The Ice House will be open a few hours on Sunday morning. The price will be eight and a third cents a pound with an allowance of four per centum to those who purchase largely or by tickets. The price at which ice is now offered in Charleston is as low as it was in the northern cities when the article was first introduced in them in the summer season; and when it is remembered that the capital invested in this undertaking falls very little short of $10,000 and the very great waste which must necessarily take place in the best constructed ice-house it must be apparent that the profit cannot be more reasonable however great the consumption may be. The inhabitants therefore are invited to call for ice in such quantities as shall enable the proprietor of the house to continue the present price which cannot be the case unless ice is used rather as a necessary of life than as a luxury.

The best method of carrying ice in a small quantity is to wrap it in a blanket. These may be had at the ice-house of sufficient size at $ 1.00. Of the mode of keeping ice best when it is carried home it is to be observed that it should be kept in that part of the house which is least cool, that is to say in a dry closet where there is no circulation of air ... it is a well attested principle that whatever will keep a man warm, with the exception of the sun and fire, will keep ice cold.23

By 1834, the original price in Charleston of $166 a ton had dropped to $25 per ton, and the ice purchased by ice-tickets to $22.50 per ton. Once a New York sea captain attempted to sell ice there for $25 a ton; but Tudor's only real, though short-lived, competition had been by the Thayers of Boston who had forced him to drop his price temporarily to $15 a ton, but, with the Thayers removed, the prices recovered their previous equilibrium.24

Tudor had a strange combination of unshakable drive and of morbid pessimism. His eleven years of endeavor to establish firmly the ice business had left him disillusioned and cynical. From Charleston he wrote to his brother-in-law, Robert H. Gardiner,

I most sincerely and heartily regret that you have arrived at a view of life similar to my own, although not precisely the same. It is more than two years since I became satisfied in my mind of the absolute worthlessness of our existence here, and the difficulties I have passed through, which to give them a mild term have been horrible, have not had a tendancy to lessen or soften this opinion . . ,25

1818 saw Tudor advancing down the Southern coast to offer ice to Savannah, Georgia. That and the following year improved financially for him, as Tudor himself tells of his good fortune in a letter under date of September 16, 1819 to Samuel Parkman who held a mortgage on a piece of Tudor's real estate. Tudor told Parkman that he had already sold $30,000 worth of ice that year and that he expected to sell another $6,000 or $8,000 worth before the end of the year. At that time his ice-houses - of which he had four - cost $10,000 each, as well as being extensive in the ground they covered. They were, as well, insured against fire for $6,000. In short, Tudor considered himself a rich man.26

Nine months later, however, he wrote that he was without a dollar; perhaps due in part to the depression of 1819-1820.27 During that year he made another march along the Atlantic Coast and into the Gulf of Mexico by sending ice to New Orleans, where Harry Tudor cared for the local business. Ice eventually sold there at $40 a ton - quite cheaply considering Tudor paid between $435-$600 freight per small brig-load of ice.28 The combination of his losses and the news of further embarrassments cropping up in the West Indies prompted him to write in February 1821 that so far as his ice business was concerned, "To lift it up again is past my ability." The preceding twelve months, he went on, had brought him from a rich man to being practically bankrupt. His sales were falling off everywhere. In Havana, his best market, the trade had fallen off by one-half, at Charleston and at Savannah by one-third, and his venture at New Orleans was beginning on borrowed money. To ship more ice is impossible, he complained, "It is done! It is finished!" Tudor informed his agent that the latter had better tell the Martinique government that in the course of three years the company had lost $25,000. The government of St. Thomas, furthermore, should be told that they had received their last shipment. If only he could realize $1200, Tudor said, he could perhaps get out one last cargo, but as he was heavily in debt and saw no means open to him, he considered his business was verging on collapse.29

Although Tudor's investments were in trouble, they were not insoluble. His perspective was not distant enough to see that, however, and in 1822, after the strain of seventeen years in such a shaky pursuit, he suffered a nervous collapse. His brother-in-law, Robert H. Gardiner, who, by Tudor's own admission, was one of the few people who had believed in him and had remained by him throughout the years, nursed him back to health, and during Tudor's recovery managed the business for him.30

The recovery was speedy, and within a short time Tudor was back facing more and newer difficulties. His profits or losses depended largely upon Nature, and the risk he faced was inevitable. "The frost covers the windows," he once remarked, "the wheels creak, the boys run, winter rules, and $50,000 worth of Ice floats for me upon Fresh Pond."31 In 1828, however, coastal Massachusetts reveled in a mild winter while Tudor cursed and made frequent excursions to his ice ponds to see if they were freezing over. He soon realized that enough ice from his regular ponds could not be cut that winter, and so he arranged with Robert H. Gardiner to get a supply from the Kennebec River in Maine. Tudor would make little money from the proposition, but at least he expected to keep open his commercial avenues. As there was little demand in Maine for Massachusetts produce, ships going up to the Kennebec would have to go in ballast, thus necessitating freight charges for both legs of the trip. As luck would have it, much of the Kennebec ice, which had been stacked on the shore, was lost during a spring freshet, and Tudor fell on short rations.32 Reputedly, when supplies ran short at Martinique, the captain of the brig Retrieve sailed north towards Labrador, where he and his crew bodily mutilated a passing iceberg to fill the ship's small hold.33

Up to this time, Tudor's endeavors had been restricted to ports requiring relatively short voyages. In 1833, he determined to try a more enterprising venture, and, accordingly, he dispatched 200 tons of ice to Calcutta on the ship Tuscany.34 A Calcutta historian, in speaking of the ice, eulogized, "I will not talk of nectar or elysium, but I will say that if there be a luxury here, it is this - it is this. ... A block of pure ice weighing 2 maunds," he continued, "was a sight Calcutta had never seen before."35 The only ice that had ever before been seen in Calcutta was a Hooghly-Plain ooze made by skimming surface ice from water in unglazed pots placed overnight in reed-lined pits.36 For once, Tudor was not faced with raising enough money to construct an ice-house. A Calcutta gentleman believed that if the inhabitants of Calcutta would provide an ice-house for the use of an importer, ice might be procurable all year round at a reasonable price. He reported: "Acting upon this belief, I wrote to Mr. Frederick Tudor ... He accepted the terms . . . The idea of having the purest ice at three halfpence a pound during the whole year, instead of having the Hooghly slush for six weeks at fourpence the pound, was irresistable." The ice-house was built, and when Tudor's first cargo thereafter arrived, the building was turned over to his agent. "The regularity of the supply has been twice interrupted, one ship having been wrecked at the Sandheads and another burnt at sea; but for the last nine years there has not been any interruption."37 This last was written probably in the late i84o's.

One of the first of the shipments to India, made by Captain Codman in the ship Nantasket, brought disbelief and amazement to the large crowd of natives gathered at the wharf to witness the unloading of these "crystal blocks of Yankee coldness." One of the Indians braved to touch a piece of the ice, and, believing that he had burned himself, wrapped his hand in his robe and rushed away followed by a number of the alarmed onlookers. At another time, a native was supposed to have asked Captain Codman, "How this ice make grow in your country? Him grow on tree? Him grow on shrub - how he make grow?"38

The story of ice in India is by no means complete, but what remains must be left for the time when Tudor began to face serious trade competition, and the ice from one particular lake - Wenham Lake - became famous around the world. It is enough to mention that Tudor's ice venture came at the crucial time to save Boston's East India commerce from ruin. Only the slightest hold had been retained in Bengal by the Boston and Salem merchants, and that only by exporting specie, Penobscot salmon, cods' tongues and sounds, coarse glassware, and Cape Cod Glauber salts.39

Tudor's last virtually competition-free expansion took place in 1834 when he shipped a cargo off to Rio de Janeiro in the bark Madagascar.40 The competition had begun many years before, but Tudor had always managed to eradicate it before it could get a foothold. By the late i820's, Tudor felt the effects of considerable competition. He willingly put into action a "boom-or-bust" price-war to rid himself of it. "The coast is now cleared of interlopers," he reported at last, "good and substantial foundations laid ... If there are any unslain enemies, let them come out. . . ."41 Beginning about 1836-7, however, Tudor found that he could no longer prevent competition from forming and still remain in business. By 1855, there were twelve companies engaged in the ice trade in and around Boston.42

The growth of the trade can be seen from the fact that in 1806, 130 tons were exported; in 1826, 4,000 tons; and, in 1856, the figure had risen to the phenomenal height of 146,000 tons. The jump in tonnage during the ten years between 1846 and 1856 had been 81,000 tons. Tudor never could have handled such a volume alone - competition must, to a great degree, have accounted for the rise.43

Tudor's exclusive part thus ended. Although he died in 1864, the Tudor Ice Company carried on the name for a number of years thereafter. At one point in Tudor's incredible career, he had owned ice-houses all over the world - in Havana, Jamaica, New Orleans, Charleston, Mobile, Calcutta, Madras, Bombay, Galle, and Singapore.44 There will be occasions to speak of him and his company again, but, from the early 1840's on, however, the trade was for others to enlarge.

There were nine main sources of ice around Boston. Some ice came from the Kennebec and Penobscot Rivers in Maine, but the local supplies centered around Fresh Pond, Cambridge; Smith's Pond, Arlington; Spy Pond, Arlington; Sandy Pond, Ayer; Horn Pond, Woburn; Lake Quannapowitt, Wakefield; Haggett's Pond, Andover; Suntaug Lake, Lynnfield; and Wenham Lake, Wenham.45

Henceforth, our attention will be directed towards the last of these - Wenham Lake - for, after one or two false starts, ice from this small lake became world-famous and graced the tables of the aristocracy of plush London society. It is said without undue exaggeration that no dinner party in London was considered complete without ice from Wenham Lake. It is more than likely that some ice shipments were called "Wenham Lake Ice" when they were erroneously labelled, but it was, after all, Wenham Lake ice that achieved recognition over all other ice exported from the United States. Its purity was remarkable, and its ability to withstand temperature changes that would have reduced other ices to mush makes the story all the more interesting.

The question most frequently asked is how did the ice withstand the voyages, and how much of the ice was lost due to meltage? The answer to the latter is by no means clear, although it is known, for example, that the vessel Arabella in 1854-5, on a voyage from Boston to Calcutta, arrived at that port with only thirty-eight tons out of an original 160, or, a loss of just over 76% .48 Another instance records a loss of 176 tons on a fifty-one day passage to England in 1852, the daily average lost amounting to 3.451 tons.47 Although these losses appear large, they were not as bad as they might seem when it is remembered that, on the average, only forty to fifty blocks of ice were necessary to make a ton. The water lost from the ice was not enough to endanger a vessel, for, from the last example, 3.45 tons of ice represents approximately 793 gallons or about 4.7 cubic feet of water daily which the ship pumps could easily have handled. The ice lost on that voyage amounted to only 35%. It has already been noted, not in connection with Wenham Lake ice, that in 1807 Tudor lost 50% of his cargo between Boston and Havana. It can be seen, therefore, that there was no one answer to the amount of ice melted en route, but the amount varied according to the conditions and voyage lengths.

It was early claimed that Wenham Lake ice could withstand temperature changes that other ices could not have endured, and many elaborate explanations were devised to account for that property. Purity of water was the most plausible of all; in fact, it was claimed that the ice was so clear and transparent a newspaper could be read through a block two feet thick.48 Even if the figure is an exaggeration, it is true that ice formed on Wenham Lake was unusual.

The most authoritative explanation was proposed in 1849 by a visiting Englishman, Sir Charles Lyell, F.R.S., a geologist of repute. "The water is always clear and pure," he wrote, "and the bottom covered with white quartz-zose sand. It is fed by springs, and receives no mud from any spring flowing into it; but at the lower extremity a small brook of transparent water flows out. In some parts, however, there must, I presume, be a soft and muddy bottom, as it is inhabited by eels, as well as by pickerell and perch." Sir Charles continued to cite the opinion of Sir Francis Head, who, in 1835, had become the lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada. Head attributed the durability of Wenham Lake ice to the intense cold of the North American winter. Sir Charles quoted Sir Francis as saying,

People in England are prone to think that ice is ice; but the truth is, that the temperature of 32° Fahrenheit, that at which water freezes, is only the commencement of an operation that is almost infinite; for after its congelation, water is as competent to continue to receive cold, as it was when it was fluid. The application of cold to a block of ice does not, as in the case of heat applied beneath boiling water, cause what is added to one end to fly out at the other: but, on the contrary, the centre cold is added to and retained by the mass ... if two ice-houses were to be filled, the one with Canada ice, and the other with English ice, the difference between the quantity of cold stored up in each would be as appreciable as the difference between a cellar full of gold and a cellar full of copper; that is to say, a cubic foot of Lower Canada ice, which again contains more cold, than a cubic foot of Upper Canada, which again contains more cold than a cubic foot of Wenham ice, which contains infinitely more cold than a cubic foot of English ice; and thus, although each of these four cubic feet of ice had precisely the same shape, they, each, as summer approaches, diminish in value; that is to say, they each gradually lose a portion of their cold, until, long before the Lower Canada ice has melted, the English ice has been converted into luke-warm water.49

Lyell, however, was not satisfied with Head's explanation. He put forward his own and more scientific reason for the durability of Wenham Lake ice:

. . . each fragment of ice, when removed from the storehouse, very soon acquires the temperature of 32° Fahrenheit, and yet when a lump of Wenham ice has been brought to England, it does not melt by any means so readily as a similar lump of common English ice. Mr. Faraday tells me that Wenham Lake ice is exceedingly pure, being both free from air-bubbles and from salts.50

Lyell illustrated his opinion by referring to an established principle of Physical Optics. If a piece of Wenham ice and a piece of English ice were each ground into lenses which would, like magnifying glasses, concentrate light rays into a focus, the Wenham ice, being free from interfering air-bubbles, if focused properly, could ignite a charge of gunpowder. The lens made of the impure English ice, however, if it were to be focused on gunpowder, would fail to explode it because the impurities would prevent the sun's rays from being concentrated into a point. As Wenham ice was remarkably free from salts, it....

...conduces greatly to the permanence of the ice, for where water is so frozen that the salts expelled are still contained in air-cavities and cracks, or form thin films between the layers of the ice, these entangled salts cause the ice to melt at a lower temperature than 32°, and the liquified portions give rise to streams and currents within the body of the ice, which rapidly carry heat to the interior. The mass then goes on thawing within as well as without, and at temperatures below 32°, and only on the outside of the mass.51

Ice was packed aboard ship with wood shavings, sawdust, or rice chaff on its outside surfaces to insulate it against heat. The blocks were also stacked together like well-fitted masonry. The greater volume of the cakes, therefore, could be considered as being the interior of one huge block, leaving relatively small amounts of the ice on the outside to melt by whatever heat penetrated the sawdust covering.

In 1842, the firm of Gage, Hittinger & Company was established and proceeded to give the Tudor Company competition. Although Gage, Hittinger & Co. did not become prominent in the exportation of Wenham Lake ice until 1850, its first trans action in 1842 with ice from Fresh Pond, Cambridge, merits mention, for it was the first attempt to introduce American ice into the markets of England.52

London, up to that time, was obliged to draw its meager and unsatisfactory ice supply from shallow reservoirs where ice was allowed to form during the winter months. An 1850 issue of the Illustrated London News shows a group of people hauling carts through the countryside to collect thin slabs of snow-ice found along the road. These they would later sell for exorbitant sums but the ice was slushy and was not fit for close contact with food. The purity and cleanliness of Wenham Lake ice was always stressed, conversely, as fit for "table use."

In 1842, Gage, Hittinger & Company, proposed to supplement England's small ice supply by shipping a cargo of Fresh Pond ice to London. Hittinger went ahead on a steamer to prepare for the shipment's arrival and, arriving in London, established his contacts and talked over the venture with interested persons. As he said, he "felt perfectly sure that" he "had struck a vein." In due course, the ice shipment arrived on the bark Sharon, heralded by vigorous advertising in the London Times. Hittinger continued;

.....but, after all, it appeared to them a strange fish that no one dared to touch. My feelings were just about the temperature of the ice, and wasting as rapidly. At last, I was introduced to the Chairman or President of the Fishmonger's Association, an association which I was not long in discovering had the merit of wealth, if not of social position. He was sociable, and seemed to comprehend my position if I didn't his. Matters were soon arranged; a magnificent hall or saloon had been secured; I ascertained that my barkeepers, through constant drill, had attained the correct sleight of hand in mixing the drinks. The hour arrived. The hall was long and brilliantly lighted. After the company was seated, the chairman introduced me and the subject matter of the evening's discussion. Now, thought I, I am all right. At a given signal the well-trained waiters appeared, laden with the different drinks. The effect was gorgeous, and I expected an ovation that no Yankee had ever had. But, alas! the first sounds that broke the silence were: 'I say -, aw, waitaw, a little 'ot wataw, if you please; I prefer it 'alf 'n 'alf.' I made a dead rush for the door, next day settled my bills in London, took the train for Liverpool and the steamer for Boston, and counted up a clear loss of $1,200.53

Despite the inauspicious beginning in England, American ice was fated within a few years to become an article very much in demand by English society - Wenham Lake ice in particular. It would be well to bear in mind Frederick Tudor's observation that ice had always been unsuccessful when first introduced anywhere, but, as time went on, the demand for it advanced greatly.

Evidently, Charles B. Lander of Salem had similar thoughts, for he refused to accept Hittinger's failure as an indication of the potential of American ice in England. He prepared, nevertheless, to extract ice from Wenham Lake for the London market. Gage, Hittinger & Company was not to make money from the benefits of Wenham Lake for seven years thereafter.54

In 1842-3, Lander began the construction of several ice-houses on the northeast shore of Wenham Lake.55 One of these had once been the Meeting House of the town, built in 1748 and later moved to the side of the Lake. For the enterprise to be a success, however, Lander was obliged to negotiate with the Town for land on which to erect these ice-houses, as well as for a strip of land adjacent to the small hill - on which Hugh Peter had preached to the Indians - so that a spur railroad track could be built to connect the ice-houses to the main railway line about one-fourth of a mile to the east. The Town Records of Wenham tell the story of the progressive concessions to Lander. In November 1843 it was voted that the Town grant Lander enough land next to Peter's Hill for the construction of the spur railway line and that the Selectmen were to turn it over to him in return for compensation. It was further voted, however, that the Town would not sell land to the east or to the south of Peter's Hill for the location of ice-houses. At the next Town Meeting in March 1844, the question came up as to whether or not Lander was to be permitted to buy Peter's Hill. Twenty-two favored the sale by the Town; forty-two were opposed. The next month, in April, another meeting was held, and the question of the sale of Peter's Hill was reconsidered. This time, thirty-five voted in favor of the sale, and only twenty-nine opposed. Thus, Lander was permitted to buy Peter's Hill, bounded on the east by its base, for $75.00 . The remainder of the land between the east base of the hill and the "new building" was to be sold to Lander for $25.00 .56

Lander's ice-houses were located on the small cove at the northeast edge of the Lake, close by the road connecting Wenham to Beverly and Salem (now Route IA), and as near to the main line of the Great Eastern Railroad as was convenient. These ice-houses stood at the water's edge, lined up in a row and covered with stagings and slides to facilitate the entrance of the ice. Sir Charles Lyell described them as covering an area of 127 feet by 120 feet to a height of about twenty-four feet. The nearest building to the road was crowned by a cupola, and in that structure hung a bell for signaling the workmen.

During the early months of 1844, Lander cut and stored the ice he intended to ship to England later in the year. One would think that getting ice from a small lake would consist of the simple process of waiting until the pond had frozen over to the thickness desired and then sending out horses and gangs of men to cut it. But it is not as uncomplicated as it might seem. Once the lake had frozen over to a degree that it could support a man's weight, there was generally a snowstorm which deposited several inches of snow over the surface of the ice. The workmen then went out onto the ice and cut through small holes over the entire area at a distance every few feet. That was known as "sinking the pond," and by drilling holes at regular intervals through the ice, the water from below was allowed to spread up over the top surface to turn the layer of snow into ice. Soon, after a week or more of extremely low temperatures, the ice would have formed into an average thickness of fifteen inches. An acre of foot-thick ice yielded about 1000 tons of rough ice, which, after cutting, would be trimmed to eliminate the spongy ice on the extremities. A block of top-surface area of forty-four square inches, after such trimming, was often reduced to twenty-two square inches by the time it was loaded aboard the railroad cars to be taken to the wharves in Charlestown for shipment.57

Lander found that the ice business required more capital than he had anticipated. He had raised $10,000, but more was required to keep the endeavor from failing before it had started. Accordingly, in March of 1844, he sold an interest in the Wenham Lake Ice Company to George Wheatland and Judge Joshua H. Ward, both of Salem. With the improved financial conditions of the company, final operations were made possible, and toward the end of May and at the beginning of June, Wheatland supervised the shipment of ice and the loading of the ice-cars that rolled back and forth between Wenham and Boston carrying the ice blocks to the bark Ellen. Lander, in the meantime, left for England to prepare for the arrival of the cargo.68

The Ellen left Boston for Liverpool on June 10, I844.59 Her arrival at that port was noted in the London Morning Chronicle on July 10 as having reached Liverpool on July 9. This brief notice in the column of "Shipping Intelligence" of the arrival of the Ellen was quite ordinary - no mention at all was made of her unusual cargo. Gratifyingly enough, the product began to become popular, and on the 13th of August, another cargo of Wenham Lake ice was shipped to Liverpool on the Concordia.60 She arrived on September 12th, after a passage of thirty days.

Many contemporary English descriptions of Wenham Lake ice have come to light and will be mentioned, but one of the most comprehensive of these is this:

This commodity which was first introduced to the notice of the English public a short time ago through the medium of the Liverpool Press, is so rapidly advancing in popularity in the metropolis that no banquet of any magnitude is considered complete without it. It has become an essential element in the civic fetes of Lovegrove; at the London Coffee House, Ludgate Hill, at Blackwall, at the London Tavern, Bishopsgate Street; the Albion, Aldersgate Street; Long's Hotel; and in fact, at every establishment of a similar kind of any celebrity in London. Not only is the Wenham Lake ice coming into vogue as a luxury among the aristocracy, but it is also recommending itself to the middle classes as a necessity, and even to the humbler ranks of life as an article of economy. As a preservative of food, whether in a raw or a cooked state, it is of the greatest possible utility, the price of the ice being nothing compared with the value of the provisions it secures against corruption.61

Some mention has already been given to the methods employed in "sinking the pond" to help the ice freeze to the desired thickness. A few brief remarks, then, must be added concerning the techniques used to cut the ice, to store it, and to ship it to the exporting vessels.

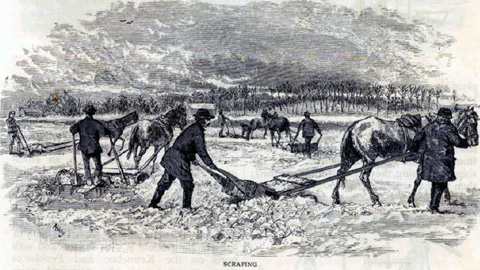

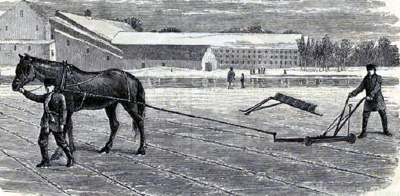

Once the ice had frozen thickly, all porous ice and snow on the top surface was removed by means of a horse-drawn plane or scraper.

Scraping Off the Snow

Planing Off the "Snow Ice"

Marking the Ice for Plowing (plow is upside down in background)

Sawing and "Barring Off" the Floats

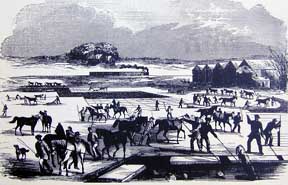

All Operations Going on at Once - Spy Pond Cambridge, Massachusetts

When the area was cleared of all sludge, the surface was "grooved" into blocks by a knifelike plow drawn by a horse. That lined the ice with shallow furrows, indicating at which points the cakes were to be cut. The workmen then went onto the ice and separated the cakes with hand saws; then loosened the floes with a needle-like crowbar.

These blocks were poled toward the icehouse elevator to be hauled up - in the early days by horse power, but later by steam. The stagings shown on an old photograph of the ice-houses on Wenham Lake were, in effect, slides, up which the ice could be pushed to varying levels depending upon the height of the ice blocks already in storage within the ice-houses. Once inside, the blocks were piled together as closely as possible to prevent all unnecessary meltage. A further protection was afforded by the construction of the ice-houses themselves. It will be recalled from Tudor's Havana ice-house that two dimensions were given - the inside dimension and the outside dimension. It is evident that a double wall of wood, a non-conducting material, provided insulation against wastage. The space between these walls was often filled with shavings, hay, sawdust, or tan, in order to further insulate the building.62

At Wenham Lake, it is probable that each of the railway cars run in by the ice-houses held only about five tons of ice each, or, about 250 blocks of ice per car. The workmen in the ice-houses pried loose the stored ice by means of chisels, the ice was loaded on the insulated railway cars and was packed off to Charlestown. Once they had arrived at the docks, each car was separately weighed and moved opposite the loading gangway of the vessel. There, a machine had been set up to load the ice onto the ship. Just above the deck level was placed a grid of beams over which was placed a horizontal windlass. Two gigs, or small platforms, were free to move up and down between the ground and the deck by means of the cable wound around the drum of the windlass. Accordingly, one of the gigs would be at ground level while the other was on the deck of the ship, and so a continuous process of loading was made possible. The average amount of ice loaded in this manner each day was about 300 tons, although it was possible to load as much as 500 tons a day if necessary.83

Wenham Lake ice enjoyed its greatest popularity in England between the year 1844 and the early years of the 185o's. It was in demand everywhere, and it grew into such vogue that London hotels put up signs informing their customers that Wenham Lake ice was served there.64 The main London office of the Wenham Lake Ice Company was located at 164A Strand, but an agency for the company was also located at 302 Oxford Street. By 1845, other agencies were located throughout England and Ireland, with offices not only in London, but also Liverpool, Birmingham, Manchester, Hastings, and Dublin. Pure and clean ice of the size of the Wenham Lake blocks was unknown anywhere in England, and the Wenham Lake Ice Company exploited the crystal qualities by advertising that the "ice is suited for table use, for mixing with liquids, or placing in direct contact with provisions, jellies, etc."65

The article was considered a wonder by the Londoners who passed the main office on the Strand. A visiting American wrote to a friend in Salem that,

I am reminded of Salem whenever I go down the Strand, by the sign of the Wenham Lake Ice Company, and a large block of ice which appears at the window. In passing the shop, the other day, on the box of an omnibus, I heard a very well-dressed person, who sat on the other side of the driver, gravely inform him that this ice came from the West Indies; very marvellous geographical knowledge! This block of ice is about eighteen inches square, and about twelve thick. The Londoners look upon it with amazement. I am told they sometimes go into the shop after gazing through the window, and put their hands on it, to be sure that it is not glass. Many consider it, likewise, a sort of standing miracle, for they don't see that it diminishes, not having a suspicion that the cunning Connecticut Yankee who exhibits it, takes a new piece out of the refrigerator every morning.66

To serve its customers better, the Wenham Lake Ice Company also sold "American Refrigerators or miniature ice-houses" so that the ice might be better preserved by the purchasers. These refrigerators, so ran the advertisement in the Times, "by the aid of a half cwt. of ice weekly, furnishes a provision safe, under the same lock, and at the same temperature, as a wine cooler, where provisions may be preserved for a long time, and wine kept always ready for use, as, undergoing no change of temperature, it may be left for weeks in the refrigerator, without the slightest deterioration."67

The "Wenham" refrigerators were nothing more than air-tight boxes, sealed by a double-lid arrangement, and containing small shelves for food on the sides of the interior. The above-mentioned advertisement, and others, constantly emphasized that these were manufactured solely by the Wenham Lake Ice Company. "All refrigerators not bearing their stamp are spurious imitations of those which the Company have, for many years, manufactured in America, and now registered in this country; and legal measures are in progress to prevent this infringement of their rights. Genuine refrigerators and Wenham Lake ice are to be obtained only from the Company and their advertised agents."68 Another advertisement followed two weeks later which again emphasized that "No refrigerators are genuine except those which bear the arms of the Company and date of registry upon an engraved die plate within the inner lid."69 A July 8, 1845 advertisement had read: "Many fishmongers and dealers in common rough ice profess to supply American ice to their customers, but it is only to be obtained from the Company's advertised agents . . ."70 Ten days later, however, the brigantine Acton delivered to Glasgow a shipment of 220 tons of New York ice, but there is no indication that it provided any threat to the Wenham Lake Ice Company, which, by that time, had become firmly entrenched.71

The company gladly shipped their ice to the London suburbs as well as to the city proper, for the lengthier deliveries were possible by wrapping the ice in blankets or other coverings to prevent it from melting en route. The city customers were urged to order at least an hour in advance of the 8 A.M. and 3 P.M. hours at which the vans left the ice-houses for their delivery rounds.72 The product shortly became widely known throughout the country.

Soon after the summer's supply of Wenham ice had arrived in London in 1845, the Illustrated London News ran a story about the company, accompanied by engravings of one of the "Wenham Refrigerators" and of the ice-houses, spur railway, and ice cutting procedure on Wenham Lake, which it called the "Wenham Ice Lake." The latter, it said, was an accurate picture that had been scrupulously made from personal descriptions by members of the Wenham Lake Ice Company. The engraving is, in fact, accurate in a number of respects, but it contains the inevitable romanticism that such a scene would elicit.

. . . Many of our town readers, have of course, seen the massive specimen of their commodity which has for some time attracted so much attention in a shop window, not far from our office in the Strand; and from the Court Circular we learn that a fragment of similarly vast dimensions was, a few weeks since, transmitted to Windsor, and submitted to the inspection of her Majesty and Prince Albert.

One surprising circumstance connected with the trade, is the fact that their Ice, though transported to this country in the heat of summer, is not reduced in bulk. Those engaged in the trade, we find, account for this by the fact that the masses of Ice are so large, that they expose a very small surface to atmospheric action in proportion to their weight, and therefore do not suffer from exposure to it, as the smaller and thinner fragments do, which are obtained in our own or other warmer climates. It appears, also, that Ice frozen upon very deep water, is more hard and solid than Ice of the same thickness obtained from shallow water; and even when an equal surface is exposed, melts more slowly . . .

The peculiar and ascertained purity of the Ice used in America, fits it for table-use; and it is accordingly the constant custom there, to mix it with water or milk, for drinking; to dilute it with wines or spirits, and to place it upon the table, in direct contact with butter and jellies. Some of our hotels and taverns are beginning to use this Ice for the manufacture of "Mint-juleps," "Sherry-coblers," and other American beverages of celebrity; and we should not be surprised, if these tempting drinks, as well as the Ice itself, were to come into very general use. . . .73

The Court Circular, widely known and read by all Englishmen, was a daily newspaper column giving running accounts of the Royal visitors and happenings at Court. It is said that Queen Victoria was so impressed with her sample of Wenham Lake ice that she thereafter insisted that it always be made available to her.

The best index of the popularity and of the great impression made by Wenham Lake ice - not to mention the fact that it was assumed everyone knew about it - is found to be London's humor magazine, Punch. A cursory examination of its volumes for 1845 and 1846 have brought to light six references to the ice, all of which seem to have been overlooked until now.

JUNE 1845

A concern has lately started in the Strand, under the title of the Wenham Lake Ice Company. The stock of the company appears to consist of large blocks of ice, so that great care must be taken not to melt the whole of the capital. We do not quite understand what the object of the company may be, or whence the profit is to be derived; but the enormous lumps of ice look as if they were intended to pave the streets, the ice would, no doubt, prove a formidable rival to the wood, if the former should be brought into competition with the latter. The only question would be, as to the durability of the ice, though its hardness seems to denote that it has many of the properties of friezestone.

By the way, the Wenham Lake Ice Company might make a very excellent speculation of laying down the Serpentine, or some other popular river, with ice, for the benefit of skaters between the bathing and the skating seasons. We recommend the directors to look to this as speedily as possible. We presume there is a sunshine company at the North Pole; for if it is possible to have a Wenham Ice Company in full play in the Strand during the dog-days, it may be perfectly practicable to establish an emporium for heat in the coldest climates.75

AUGUST 1845

Considerable curiosity has been excited as to the immediate objects and future prospects of the Wenham Lake Ice Company, recently established in the Strand. An established wag, who stands unusually high in the facetious world, has given it as his opinion that the ice must be poisonous, for it is openly advertised as Concentrated Wenom (Wenham).

We understand, however, that the real object of the Wenham Lake Ice Company, and the one by which it is expected that the largest profit will be realized, is the paving the metropolis with large blocks of the article, which will be found almost as durable as the wood pavement, and not quite so slippery.76

MAY 1846

We have read in the papers recently, several paragraphs announcing the recent importation of ice, to an extent that is quite unparalleled. The cargoes that are continually arriving cause us very naturally to inquire what is going to be done with all the ice that is being "entered inwards" at the Custom House? It cannot be all intended for being "entered inwards" in the shape of ice-creams during the ensuing summer; and though every small greengrocer boasts of ginger-beer kept continually in ice, still the superabundance of the article imported would be sufficient to cause an inundation of the markets. It is evident, therefore, that something beyond the reduction of cream to a gelid state, or the freezing of Imperial pop, must be contemplated by those speculators who are introducing ice by shiploads into England. We are inclined to believe that the Wenham Lake article, which is brought in the form of substantial blocks, may be intended as a substitute for the wood pavement. There is no doubt that the ice would be an improvement on the wood; for the latter has all the slippery qualities of the former, without any of its more desirable attributes.

Another very feasible suggestion with reference to the destination of the Wenham Ice, is, that its importation may have something to do with Dr. Reid's Ventilating experiments. The professor may possibly require a few cargoes of ice to enable him to cool down the atmosphere to a degree required for Parliamentary consumption.

Another opinion seems to be, that the ice is intended for workhouse use, as it has been ascertained by Dr. Reid that persons in a freezing temperature feel a total prostration of the appetite. At all events, it is a mystery to us, for all this ice seems quite incapable of solution.77

JULY 1846

You must recollect, Mr. Punch, the state of the thermometer during the past month - generally between eighty and ninety degrees in the shade . . .

It makes my heart bleed to witness the protracted sufferings of these large, plethoric men; one of them a Hall Porter, of mature age and startling obesity. There they stand, on the steps before the street door, making passers-by wink and nursery-maids blush at the splendor of their attire - white, scarlet, and gold - perspiring exceedingly, and irritated to madness by the blue-bottle flies and impudent little boys of the vicinity, who unceasingly exclaim, with exasperating monotony, 'I say, BLAZES, vy don't you buy a Wenham 'frigerator?'78

AUGUST 1846

The LORD MAYOR presents his compliments to the Clerk of the Weather, and begs to inform him, that, having a private dinner party at the Mansion House on Saturday next, at six, and being unable, after repeated applications, to get any ice from the exhausted stores of the Wenham Lake Company, that, should the Clerk of the Weather have remaining by him any small pieces calculated for mixing in sherry cobblers, and could send a supply into London about that time, the LORD MAYOR will feel himself deeply indebted to the Clerk of the Weather.79

During the decade of the 1840's, the Wenham Lake Ice Company, in Wenham, notwithstanding its successes in England, changed hands at fairly regular intervals, Lander sold out to George Wheatland, who, in turn, sold the company to Nathaniel West. West then transferred it to Francis and George Peabody, Augustus Perry, and John L. Gardner. Finally, in 1850, the whole business was bought out by Gage, Hittinger and Company.80

Before leaving the successes in England, a few last remarks must be made. By 1850, although ice was still sent from Wenham Lake to England, the volume shipped had greatly diminished, and during the previous year, London had received more of her ice from Sweden and Norway than from Wenham.81 Evidently, the ice from these countries could be harvested and delivered more cheaply than that sent from Wenham. It seems that in order for the trade name of "Wenham Lake Ice" to be continued. Lake Oppegaard in Norway was bought and rechristened "Lake Wenham." There, ice was cut for about five shillings a ton. By the time it had reached England, the cost to the consumers had risen to between eighty and 100 shillings per ton, or, roughly, between $20 and $25 a ton.82

How many banquets and state occasions in England had used Wenham Lake ice? William Makepeace Thackeray crowns the story;

As for describing, then, the mere victuals on Timmins's table, that would be absurd. Everybody - (I mean of the genteel world of course, of which I make no doubt the reader is a polite ornament) - Everybody has the same everything in London. You see the same coats, the same dinners, the same boiled fowls and mutton, the same cutlets, fish, and cucumbers, the same lumps of Wenham Lake ice, etc. . . . Can't any one invent anything new?83

We recall that Frederick Tudor began sending ice to India in 1833. Wenham Lake ice, in time, began to find its way to Indian ports to become almost as well known there as in England. Do you recall Rudyard Kipling's story entitled "The Undertakers" from the Second Jungle Book?

"From the insides of this boat they were taking out great pieces of white stuff, which, in a little while, turned to water. Much split off, and fell about on the shore, and the rest they swiftly put into a house with thick walls. But a boatman, who laughed, took a piece no larger than a small dog, and threw it to me. I - of all people - swallowed without reflection, and that piece I swallowed as is our custom. Immediately I was afflicted with an excessive cold which, beginning in my crop, ran down to the extreme end of my toes, and deprived me even of speech, while the boatmen laughed at me. Never have I felt such cold. I danced in my grief and amazement till I could recover my breath, and then I danced and cried out against the falseness of this world; and the boatmen derided me till they fell down. The chief wonder of the matter, setting aside the marvellous coldness, was that there was nothing at all in my crop when I had finished my lamentings."

The Adjutant had done his very best to describe his feelings after swallowing a seven-pound lump of Wenham Lake ice, off an American ice-ship, in the days before Calcutta made her ice by machinery, . . 84

The shipments of ice to India were probably carried on by the Tudor Company, with Tudor acting as the agent and shipper to the ice concern at Wenham, although Gage, Hittinger and Company may have carried on a certain amount of the shipping themselves. Most of the vessels mentioned in shipping histories as having carried ice, however, belonged to the Tudor Company.

One of the most important features of the trade between Boston and Indian ports was the length of the voyages. Obviously, the shorter the voyage could be made, the less ice would melt on the way. Generally, when cargoes, other than ice, were sent to India, merchants were not particularly concerned with the length of the outward leg of the voyage, but were more interested in the length of time required to sail to Boston from India. With a cargo of ice, however, the interest in voyage lengths was reversed, with the outward leg being the most important. An analysis of the times recorded by twenty-five ships making a total of thirty-six voyages from Calcutta to Boston shows that the average run was 102.5 days, with a record of eighty-one days made by the Witch of the Waves.83 (Only a few of the twenty-five were ice-carrying ships.) The record from Boston to Calcutta, however, was eighty-six days, and the average time often ran just even or slightly more than that of the return trip.86

The following list of ships represents some of those known to have been engaged in the ice trade at one time or another:

Arabella - 696 tons. Made several trips - Boston to Bombay, Calcutta and return - 17 July 1853 to 4 Oct. 1854. Took 141 days from Boston to Bombay. Boston to Madras, Calcutta and return -29 Nov. 1854 to (ca.) 23 Nov. 1855. Outward cargoes of ice, return cargoes of saltpeter, cow hides, gunny bags, jute, cloth, goatskins, shellac, dye, linseed.87

Coringa - Rerigged as a bark in 1874 and chartered by the Tudor Company for a cargo of ice for Calcutta.88

Elizabeth Kimball - Medium clipper, built at Marblehead in1853. The maiden voyage was a round trip between Boston and Calcutta with an outward cargo of ice.89

Harmonia - Carried ice to the East Indies for the Tudor Company.90

Iceburg - 1135 tons, built for the Tudor Company and shipped ice for several years before she was sold. Launched in i877.91

Iceking - Launched a few weeks after the Iceburg for the Tudor Company.92

Iceland - Launched a few months after the Iceking for the Tudor Company. In March 1878 she was listed as missing.93

National Eagle - Medium clipper, 1095 tons. After 1854 made frequent trips to India with ice. This was one of the best known of the ice ships.94

Reporter - Medium clipper. In 1854 was chartered by Gage, Hittinger & Co. to take ice to New Orleans.95

Springfield - Launched in 1868, 1043 tons. Took ice to Bombay on her maiden voyage96.

White Swallow - Left Boston in 1871 for Hong Kong with 1015 tons of Tudor ice. 19 days later was abandoned at sea.97

Young Mechanic - 1375 tons. In 1865 chartered by the Tudor Co. to take ice to Madras and Calcutta. Again chartered in 1866, but ship caught fire and was destroyed.98

Ice was so prized by the English inhabitants of India that its importation was encouraged as much as possible by special treatment of the ice ships. At Bombay, for example, "The only port charges on Ice ships are tonnage dues and police fees, and you get the best berth in the harbor."99 The port charges amounted to a pilotage fee of 110 Rupees during the southwest monsoon. During the northeast monsoon, the charge was 55 Rupees for vessels over 500 tons. The lighthouse dues amounted to 15 Rupees per 100 tons, the tonnage duty was one anna per ton, and the police fees were ten Rupees, two an.100 One Rupee was worth about 5o cents.101

At Madras, ice was to be found among the list of articles admitted duty-free. In fact, it was the fifth article on the list, the first two being: i) Bullion and Coin, and 2) Precious Stones and Pearls.102

As at Calcutta, Frederick Tudor was given a twenty year lease beginning in 1845 on the Madras ice-house, which was open every day during the daylight hours and for a few hours on Sunday morning.103 Madras preserved her ice-house longer than did Calcutta. According to the Calcutta historian,

Today [1907] the visitor will search in vain in Hare Street for the strangely-shaped globular building which stood perched on the summit of a flight of steps and challenged the attention of every passer-by. It was razed to the ground in 1882, and even the memories of the murder committed within its walls have faded away. Madras still preserves the shell of her ice-house. Calcutta has been more iconoclastic, and not a vestige remains of the once familiar structure in which for nearly fifty years she hoarded her precious frozen blocks from Wenham Lake.104

A curious sideline of the ice-trade to India was that New England Baldwin apples were often shipped in barrels among the blocks of ice. The clipper Elizabeth Kimball shipped such apples with her cargo of ice, for in India apples found such a large market among the English population that they were sold for fifty to seventy-five cents apiece.105

By the early 1850'$, Wenham Lake ice ceased to be shipped overseas, and the trade consisted mainly of the local markets and those found along the southern coasts of the United States. Throughout the years, ice from small lakes like Wenham Lake had made a deep impression abroad. When Edward Everett was minister to the Court of St. James in London, he once met the Ambassador from Persia who expressed his gratitude to America for shipping ice to Persia.106 The amount of ice shipped from Wenham was enormous and understandably created false ideas as to the size of the lake.

An American gentleman recently informed me that, while proceeding up the Red Sea in one of the East India Company's steamers, an Englishman, who had travelled much in America, inquired particularly of him, where Wenham Lake was situated, remarking that he had seen most of the lakes in the United States, but never saw Wenham Lake. From the amount of ice which it produced, he supposed it to be one of the large lakes of the Western Continent, and was not a little surprised when informed of its real size.107

Although the firm of Gage, Hittinger and Company had bought the ice establishments on Wenham Lake in 1850, the following year the company became Gage, Sawyer and Company, the members being Addison Gage, Timothy Sawyer, Dr. Henry Lyons, and Thomas G. Frothingham who soon died. It was said that Gage, Sawyer and Company, during one year, had loaded nearly a vessel a day for each working day.108 Eight years later in 1859, the name of the firm again changed, now to the Addison Gage & Co., with its main headquarters at 70 State Street in Boston.109 Gage's only partner by this time was his son Charles 0. Gage. Addison Gage died in 1868, four years after Frederick Tudor, and in 1871, Gage's firm took on Arthur Harrington and R. W. Hopkins, Gage's son-in-law.110 During this time, after trade with England had ceased from Wenham Lake, Gage's firm traded mostly with the Southern states. Between the years 1856 and 1882, 353,450 tons of ice had been shipped out; about 475,000 had actually been cut, but the 121,550 ton difference was accounted for by the ice lost from scraping and meltage. The average yearly amount of ice cut from Wenham Lake from 1860 to 1880 had been thirty thousand tons a year.111

In 1866, five new ice-houses were built to supplement the original ones built by Lander, but, a few years later, in 1873, a fire originating in the hay packing around the ice destroyed all of the buildings.

The light from the burning ice houses at Wenham Lake on Sunday evening, owing to the peculiar state of the atmosphere, was reflected high up on the clouds, so that it was seen from a great distance -as far off certainly as Boston, and so vividly at Newburyport as to cause a general alarm of fire. . . .

The houses destroyed were built about five years ago, at a cost of $65,000, and contained 30,000 tons of ice, valued at $25,000. The total loss is estimated at not less than $100,000, on which there was $27,950 insurance in offices out of state.112

The above figure placed the value of the ice at roughly 83 cents a ton, whereas a similar estimate in 1855 had placed the value of ice at about $1.60 per ton.113

The loss was one of the death blows to Massachusetts ice exportation. It had seriously curtailed vital parts of two firms, for Gage eventually bought out the Tudor Company, and the destruction of the valuable property at Wenham Lake necessitated large outlays of capital to restore the enterprise.114 By the time of the fire, artificial means of refrigeration were beginning to be used, and losses such as those sustained on Wenham Lake made competition increasingly difficult. The business around Wenham Lake never entirely recovered. A number of temporary ice-houses were erected, but these and others, after 1880, became almost exclusively places for the storage of ice for local markets. The original purity of the water had been sacrificed when Longham Meadow and other less crystalline water sources were emptied into the lake, which was turned into the water-supply for Beveriy and Salem. Today, it takes an unusually cold winter for the lake to freeze over to any extent beyond a thin skim.

Still, ice was cut on Wenham Lake for the Wenham, Beveriy and Salem markets well into the present century. The last of the ice-houses on the lake, that of the Metropolitan-Wenham Lake Ice Company, on the North Beveriy shore, finally disappeared around the time of World War II.

As for the Lander-Gage ice-houses, hardly a trace of them now remains. Motorists, swinging around the curve in Route IA just over the North-Beverly-Wenham town line, may notice in late summer, when the level of the lake has dropped a number of feet, several rows of stumpy, blackened pilings sticking up through the sand. Along the shore, behind the pilings, a careful observer may notice a large number of half-buried bricks, hidden under moss and leaves. These once served the famous ice-houses. Nothing more now remains.

APPENDIX & STATISTICAL INFORMATION

The Report of the Committee Appointed by the Stockholders of the Charlestown Wharf Company sheds some interesting light on the relation of freight rates on ice to its sale. (p. 8), 1839.

Ice is taken on freight, not as the foundation of a voyage;but as an incident to the voyage. A vessel would not go to New Orleans or to Calcutta, for the purpose of carrying ice, unless she charged a fair freight. But as she is determined to go (ice or no ice,) and as she frequently would go almost in ballast, so she can afford to take the ice at a low freight, and does take it at a low freight, provided she can start from a centre of general business, such as Boston harbor. This very important circumstance rivets the ice trade to Boston harbor and greatly expands its size; because the low freight enables us to sell the ice at a low price, at its point of destination; -thereby placing it within the reach of the great mass of consumers - and thereby increasing its sale a hundred fold.

PORTS TO WHICH ICE SENT IN 1856:

Philadelphia, Baltimore, Norfolk, Alexandria, Georgetown, Richmond, Wilmington, Washington (N.C.), New-bern, Charleston, Savannah, Mobile, Pensacola, Appalachi-cola, Key West, New Orleans, Franklin (La.), Thibodeaux-villa (La.), Galveston, Indianola (Texas), Aspinwall, Nassau, St. Thomas, Havana, Matanzas, Saint lago, San Juan, Barbadoes, Cardenas, Trinidad, Martinique, Guadalupe, Kingston, LaGuira, Demerara, Bahia, Pernambuco, Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, Valparaiso, Callou, Guayaquil, Ceylon, Calcutta, Bombay, Madras, Batavia, Manila, Singapore, Canton, Mauritius, and Australia.115

NUMBER OF TONS EXPORTED»

Year Amount (tons)

1806 .......... 130

1816......... 1,200

1826 .........4,000

1836 .......12,000

1846........65,000

1856..... 146,000

1860 .....142,463

1865 .....131,275

1866 .....124,751

1872 .......69,500 (approx.)

1873 .......70,370

1874 ...... 69,800

1884.........60,000

RETURN TO ICE HARVESTING USA